Butte, Montana

Butte | |

|---|---|

| Butte-Silver Bow | |

Clockwise, left to right: view of uptown Butte from west; Our Lady of the Rockies; Curtis Music Hall; aerial view of the Berkeley Pit; mine headframe; and the Finlen Hotel | |

| Nickname: Butte America | |

| Motto: The Richest Hill on Earth | |

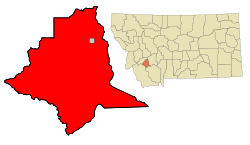

Map of Silver Bow County showing the city of Butte in red and Walkerville in gray | |

| Coordinates: 45°59′56″N 112°31′27″W / 45.99889°N 112.52417°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Montana |

| County | Silver Bow |

| Settled | 1864 |

| Area | |

• Total | 716.34 sq mi (1,855.32 km2) |

| • Land | 715.76 sq mi (1,853.80 km2) |

| • Water | 0.59 sq mi (1.52 km2) |

| Elevation | 5,538 ft (1,688 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 34,494 |

| • Density | 48.19/sq mi (18.61/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−7 (MST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−6 (MDT) |

| ZIP code | 59701, 59702, 59703, 59707, 59750 |

| Area code | 406 |

| FIPS code | 30-11397 |

| GNIS feature ID | 2409651[2] |

| Website | www |

Butte (/bjuːt/ BEWT) is a consolidated city-county and the county seat of Silver Bow County, Montana, United States. In 1977, the city and county governments consolidated to form the sole entity of Butte-Silver Bow. The city covers 718 square miles (1,860 km2), and, according to the 2020 census, has a population of 34,494, making it Montana's fifth-largest city. It is served by Bert Mooney Airport with airport code BTM.

Established in 1864 as a mining camp in the northern Rocky Mountains on the Continental Divide, Butte experienced rapid development in the late 19th century, and was Montana's first major industrial city.[3] In its heyday between the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it was one of the largest copper boom towns in the American West. Employment opportunities in the mines attracted surges of Asian and European immigrants, particularly the Irish;[4] as of 2017, Butte has the largest population of Irish Americans per capita of any U.S. city.

Butte was also the site of various historical events involving its mining industry and active labor unions and socialist politics, the most famous of which was the labor riot of 1914. Despite the dominance of the Anaconda Copper Mining Company, Butte was never a company town. Other major events in the city's history include the 1917 Speculator Mine disaster, the largest hard rock mining disaster in world history.

Over the course of its history, Butte's mining and smelting operations generated more than $48 billion worth of ore, but also resulted in numerous environmental implications for the city: The upper Clark Fork River, with headwaters at Butte, is the largest Superfund site in the nation, and the city is also home to the Berkeley Pit. In the late 20th century, the EPA instated cleanup efforts, and the Butte Citizens Technical Environmental Committee was established in 1984. In the 21st century, efforts to interpret and preserve Butte's heritage are addressing both the town's historical significance and the continuing importance of mining to its economy and culture. The city's Uptown Historic District, on the National Register of Historic Places, is one of the largest National Historic Landmark Districts in the U.S., containing nearly 6,000 contributing properties. The city is also home to Montana Technological University, a public engineering and technical university.

History

[edit]Early history and immigrants

[edit]Before Butte's formal establishment in 1864, the area consisted of a mining camp that had developed in the early 1860s.[5] The city is in the Silver Bow Creek Valley (or Summit Valley), a natural bowl sitting high in the Rockies straddling the Continental Divide,[6] positioned on the southwestern side of a large mass of granite known as the Boulder Batholith, which dates to the Cretaceous era.[7] In 1874, William L. Farlin founded the Asteroid Mine (subsequently known as the Travona), which attracted a significant number of prospectors seeking gold and silver.[7] The mines attracted workers from Cornwall (England),[8] Ireland, Wales, Lebanon, Canada, Finland, Austria, Italy, China, Montenegro, Mexico, and more.[9] In the ethnic neighborhoods, young men formed gangs to protect their territory and socialize into adult life, including the Irish of Dublin Gulch, the Eastern Europeans of the McQueen Addition, and the Italians of Meaderville.[10][page needed]

Among the migrants were many Chinese who set up businesses that created a Chinatown in Butte.[4] The Chinese migrations stopped in 1882 with the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act. There was anti-Chinese sentiment in the 1870s and onward due to the white settlers' racism, exacerbated by economic depression, and in 1895, the chamber of commerce and labor unions started a boycott of Chinese-owned businesses. The business owners fought back by suing the unions and won. The history of the Chinese migrants in Butte is documented in the Mai Wah Museum.[11][12]

The influx of miners gave Butte a reputation as a wide-open town where any vice was obtainable. The city's saloon and red-light district, called the "Line" or "The Copper Block", centered on Mercury Street, where the elegant bordellos included the famous Dumas Brothel.[13] Behind the brothel was the equally famous Venus Alley, where women plied their trade in small cubicles called "cribs."[13] The red-light district brought miners and other men from all over the region and remained open until 1982 after the closure of the Dumas Brothel; the city's red-light was one of the last such urban districts in the country.[13] Commercial breweries first opened in Butte in the 1870s, and were a staple of the city's early economy; they were usually run by German immigrants, including Leopold Schmidt, Henry Mueller, and Henry Muntzer. The breweries were always staffed by union workers. Most ethnic groups in Butte, from Germans and Irish to Italians and various Eastern Europeans, including children, enjoyed the locally brewed lagers, bocks, and other types of beer.[14]

Industrial expansion

[edit]

In the late 19th century, copper was in great demand because of new technologies such as electric power that required the use of copper. Industrial magnates fought for control of Butte's mining wealth. These "Copper Kings" were William A. Clark,[15] Marcus Daly, James Andrew Murray and F. Augustus Heinze.[7] The Anaconda Copper Mining Company began in 1881 when Marcus Daly bought a small mine named the Anaconda. He was a part-owner, mine manager and engineer of the Alice, a silver mine in Walkerville, a suburb of Butte. While working in the Alice, he noticed significant quantities of high-grade copper ore. Daly obtained permission to inspect nearby workings. After his employers, the Walker Brothers, refused to buy the Anaconda, Daly sold his interest in the Alice and bought it himself. He asked San Francisco mining magnate George Hearst for additional support. Hearst agreed to buy one-fourth of the new company's stock without visiting the site. While mining the silver left in his mine, huge deposits of copper were soon developed and Daly became a copper magnate. When surrounding silver mines "played out" and closed, Daly quietly bought up the neighboring mines, forming a mining company. He built a smelter at Anaconda, Montana (a company town), and connected it to Butte by railway. Anaconda Company eventually owned all the mines on Butte Hill.[16]

Between 1884 and 1888, W. A. Clark constructed the Copper King Mansion in Butte, which became his second residence from his home in New York City.[17] In 1899, he also purchased the Columbia Gardens, a small park he developed into an amusement park, featuring a pavilion, roller coaster, and a lake for swimming and canoeing. Clark's expansion of the park was intended to "provide a place where children and families could get away from the polluted air of the Butte mining industry."[18] The city's rapid expansion was noted in an 1889 frontier survey: "Butte, Montana, fifteen years ago a small placer-mining village clinging to the mountain side, has now risen to the rank of the first mining camp of the world... [It] is now the most populous city of Montana, numbering twenty-five thousand active, enterprising, prosperous inhabitants."[19] In 1888 alone, mining operations in Butte generated an "almost inconceivable" output of $23 million (equivalent to $779,955,556 in 2023) worth of ore.[19]

Copper ore mined from the Butte mining district in 1910 alone totaled 284,000,000 pounds (129,000,000 kg); at the time, Butte was the largest producer of copper in North America and rivaled in worldwide metal production only by South Africa.[7] The same year, in excess of 10,000,000 troy ounces (310,000 kg) of silver and 37,000 troy ounces (1,200 kg) of gold were also discovered.[7] The amount of ore produced in the city earned it the nickname "The Richest Hill on Earth."[7] With its large workforce of miners performing in physically dangerous conditions, Butte was the site of active labor union movements, and came to be known as "the Gibraltar of Unionism."[20][21]

By 1885, there were about 1,800 dues-paying members of a general union in Butte. That year the union reorganized as the Butte Miners' Union (BMU), spinning off all non-miners to separate craft unions. Some of these joined the Knights of Labor, and by 1886 the separate organizations came together to form the Silver Bow Trades and Labor Assembly, with 34 separate unions representing nearly all of the 6,000 workers around Butte.[22] The BMU established branch unions in mining towns like Barker, Castle, Champion, Granite, and Neihart, and extended support to other mining camps hundreds of miles away. In 1892 there was a violent strike in Coeur d'Alene.[23] Although the BMU was experiencing relatively friendly relations with local management, the events in Idaho were disturbing. The BMU not only sent thousands of dollars to support the Idaho miners, they mortgaged their buildings to send more.[24]

There was a growing concern that local unions were vulnerable to the power of Mine Owners' Associations like the one in Coeur d'Alene.[25] In May 1893, about 40 delegates from northern hard-rock mining camps met in Butte and established the Western Federation of Miners (WFM), which sought to organize miners throughout the West.[26] The Butte Miners' Union became Local Number One of the new WFM.[27] The WFM won a strike in Cripple Creek, Colorado, the following year, but in 1896–97 lost another violent strike in Leadville, Colorado, prompting the Montana State Trades and Labor Council to issue a proclamation to organize a new Western labor federation[28] along industrial lines.[29]

Anaconda Copper and civil unrest

[edit]

In 1899, Daly, William Rockefeller, Henry H. Rogers, and Thomas W. Lawson organized the Amalgamated Copper Mining Company.[30] Not long after, the company changed its name to Anaconda Copper Mining Company (ACM). Over the years, Anaconda was owned by assorted larger corporations. In the 1920s, it had a virtual monopoly over the mines in and around Butte.[31] Between approximately 1900 and 1917, Butte also had a strong streak of Socialist politics, even electing Mayor Lewis Duncan on the Socialist ticket in 1911, and again in 1913; Duncan was impeached in 1914 for neglecting duties after a bombing in the city's miners' hall in 1914.[32][33]

Butte also established itself as "one of the most solid union cities in America."[34] After 1905, it became a hotbed of Industrial Workers of the World (IWW, or the "Wobblies") organizing.[35] Rivalry between IWW supporters and the WFM locals culminated in the Butte, Montana labor riots of 1914, and resulted in the loss of union recognition by the mine owners.[36] After the dissolution of the Miners' Union, the Anaconda Company attempted to inaugurate programs aimed at enticing employees.[36] A number of clashes between laborers, labor organizers, and the Anaconda Company ensued, including the 1917 lynching of IWW executive board officer Frank Little.[37] In 1920, company mine guards gunned down strikers in the Anaconda Road Massacre.[38] Seventeen were shot in the back as they tried to flee, and one man died.[39]

Sparked by a tragic accident more than 2,000 feet (600 m) below the ground on June 8, 1917, a fire in the Granite Mountain mine shaft spewed flames, smoke, and poisonous gas through the labyrinth of tunnels including the connected Speculator Mine.[40] A rescue effort commenced, but carbon monoxide was contaminating the air supply.[41][42] Several men barricaded themselves against bulkheads to save their lives, but many others died in a panic to try to escape.[42] Rescue workers set up a fan to prevent the fire from spreading. This worked for a short time, but when the rescuers tried to use water, it evaporated, creating steam that burned those trying to escape.[43] Once the fire had been extinguished, recovery of the deceased began; many of the bodies were mutilated beyond recognition, leaving many unidentified.[44] The disaster claimed a total of 168 lives.[45] As of 2017, the event remained the largest hard rock mining accident in history.[46] The Granite Mountain Memorial in Butte commemorates those who died in the accident.[47]

Protests and strikes began after the Speculator Mine disaster, as well as the establishment of the Metal Mine Workers Union; about 15,000 workers abandoned their jobs in the disaster's wake.[48] Between 1914 and 1920, the U.S. National Guard occupied Butte six times to restore civility.[48] In 1917, copper production from the Butte mines peaked and steadily declined thereafter. By WWII, copper production from the ACM's holdings in Chuquicamata, Chile, far exceeded Butte's production.[49][50]

In 1919, women's rights activist Margaret Jane Steele Rozsa became a food inspector for Butte, and immediately began pressing for change to questionable practices by several county commissioners who had been keeping the community's cost of living artificially high by, among other things, allowing carloads of perishable foods to rot on unloaded trains at the railroad station.[51][52] She also "was instrumental in getting senate bill No. 19 through the legislature" that year to ensure that 199 tubercular soldiers who had served in World War I would be given "preference of entry to the Galen hospital", and that the legislature would authorize $20,000 to build additional dormitories at the hospital to make that care possible since hospital admissions were already at capacity.[53] In 1921, she became the first female prohibition inspector in the city.[54]

Open-pit mining era

[edit]

Disputes between miners' unions and companies continued through the 1920s and 1930s,[55] with several strikes and protests, one of which lasted for ten months in 1921.[56] On New Year's Eve 1922, protestors attempted to detonate the Hibernian Hall on Main Street with dynamite.[56][57]

Further industrial expansions included the arrival of the first mail plane in 1928, and in 1937, the city's streetcar system was dismantled and replaced by bus lines.[56] After the 1920s, the ACM began to reduce its activities in Butte due to the labor-intensivity of underground mining, as well as competition from other mine holdings in South America.[48] This led the Anaconda Company to switch its focus in Butte from underground mining to open pit mining.[48]

Since the 1950s, five major developments in the city have occurred: the Anaconda's decision to begin open-pit mining in the mid-1950s,[48] a series of fires in Butte's business district in the 1970s,[58] a debate over whether to relocate the city's historic business district, a new civic leadership, and the end of copper mining in 1983. In response, Butte looked for ways to diversify the economy and provide employment. The legacy of over a century of environmental degradation has, for example, produced some jobs. Environmental cleanup in Butte, designated a Superfund site, has employed hundreds of people.[59]

Thousands of homes were destroyed in the Meaderville suburb and surrounding areas, McQueen and East Butte, to excavate the Berkeley Pit, which Anaconda Copper opened in 1954.[56][48] When it opened, the Berkeley Pit was the largest truck-operated open pit copper mine in the nation.[60] It grew until it began encroaching on the Columbia Gardens.[61] After the Gardens caught fire and burned to the ground in November 1973, the Continental Pit was excavated on the former park site.[62] In 1977, the ARCO (Atlantic Richfield Company) purchased Anaconda, and three years later started shutting down mines due to lower metal prices.[63] In 1983,[64] all mining in the Berkeley Pit was suspended. The same year, an organization of low-income and unemployed Butte residents formed to fight for jobs and environmental justice; the Butte Community Union produced a detailed plan for community revitalization and won substantial benefits, including a Montana Supreme Court victory striking down as unconstitutional state elimination of welfare benefits.[65] After mining ceased at the Berkeley Pit, water pumps in nearby mines were also shut down, which resulted in highly acidic water laced with toxic heavy metals filling up the pit.[66]

Anaconda ceased mining at the Continental Pit in 1983. Montana Resources LLP bought the property and reopened the Continental Pit in 1986.[67] The company ceased mining in 2000, but resumed in 2003.[68]

From 1880 through 2005, the mines of the Butte district produced more than 9.6 million metric tons of copper, 2.1 million metric tons of zinc, 1.6 million metric tons of manganese, 381,000 metric tons of lead, 87,000 metric tons of molybdenum, 715 million troy ounces (22,200 t) of silver, and 2.9 million troy ounces (90 t) of gold.[69]

21st century

[edit]Fourteen headframes still remain over mine shafts in Butte,[70] and the city still contains thousands of historic commercial and residential buildings from the boom times,[71] which, especially in Uptown, give it an old-fashioned appearance, with many commercial buildings not fully occupied; according to a 2016 estimate, there were "hundreds" of unoccupied buildings in Butte, resulting in an ordinance to keep record of owners.[72] Preservation efforts of the city's historic buildings began in the late 1990s.[73] As with many industrial cities, tourism and services, especially health care[74] (Butte's St. James Hospital has Southwest Montana's only major trauma center), are rising as primary employers, as well as industrial-sector private companies.[74] Many areas of the city, especially those near the old mines, show signs of urban blight, but a recent influx of investors and an aggressive campaign to remedy blight has led to a renewed interest in restoring property in Uptown Butte's historic district,[75] which expanded in 2006 to include parts of Anaconda and is one of the largest National Historic Landmark Districts in the U.S., with 5,991 contributing properties.[76][77]

A century after the era of intensive mining and smelting, environmental issues remain in areas around the city. Arsenic and heavy metals such as lead are found in high concentrations in some spots affected by old mining, and for a period of time in the 1990s the tap water was unsafe to drink due to poor filtration and decades-old wooden supply pipes. Efforts to improve the water supply have taken place in the early 2000s, with millions of dollars invested to upgrade water lines and repair infrastructure. Environmental research and cleanup efforts have contributed to the diversification of the local economy and signs of vitality, including the introduction of a multimillion-dollar polysilicon manufacturing plant nearby in the 1990s.[78] In the late 1990s, Butte was recognized as an All-America City and as one of the National Trust for Historic Preservation's Dozen Distinctive Destinations in 2002.[79]

Geography

[edit]According to the United States Census Bureau, Butte-Silver Bow has an area of 716.82 sq mi (1,856.55 km2), of which 716.25 sq mi (1,855.07 km2) is land and 0.57 sq mi (1.48 km2) (0.08%) is water.[80] The city is on the U.S. Continental Divide.[6] Every highway exiting Butte (except westbound I-90) crosses the Divide (eastbound I-90 via Homestake Pass; eastbound MT 2 via Pipestone Pass; northbound I-15 via Elk Park Pass and southbound I-15 via Deer Lodge Pass).[a]

The city was named for a nearby landform, Big Butte, by the early miners.[82][83] Butte's urban landscape is notable for including mining operations set within residential areas, visible in the form of various headframes throughout the city.[84]

Cityscapes

[edit]Neighborhoods

[edit]

The concentration of wealth in Butte due to its mining history resulted in unique and ornate architectural features[85] among its homes and buildings, particularly in the uptown section.[86] Uptown, named for its steep streets,[87] is on a hillside on the northwestern edge of the town and characterized by its abundance of lavish Victorian homes and Queen Anne style cottages built in the late 19th century.[86] Several of Butte's "painted ladies" homes were featured in Elizabeth Pomada's 1987 book Daughters of Painted Ladies.[86][88] Butte-Silver Bow County has an established Urban Revitalization Agency that works to improve building façades to "enhance and promote the architectural resources of historic uptown Butte."[86] In 2017, a television pilot titled Butteification aired on HGTV, which focused on a couple restoring a Victorian home in Butte.[89]

Butte's South district, at a lower elevation than the hillside that comprises northern Butte, has historically been home to working-class neighborhoods.[90] Gold mines originally populated south Butte before it was platted for the Union Pacific Railroad in 1881.[90]

The expansion of the Anaconda Company in the 1960s and 1970s eradicated some of Butte's historic neighborhoods, including the East Side, Dublin Gulch, Meaderville, and Chinatown.[91] The St. Mary's section, which borders uptown to the east, comprised the Dublin Gulch (an enclave for Irish immigrants) and Corktown neighborhoods.[92] It takes its name from the eponymous Roman Catholic parish within it,[93] historically known as the "miner's church", scheduling masses around miners' shifting schedules.[92] Historically, the St. Mary's section of Butte had a prominent population of Slavic and Finnish immigrants in addition to Irish before the mid-20th century.[92]

Climate

[edit]Butte has a cold semi-arid climate (BSk) under the Köppen Climate Classification. Winters are long and cold, January averaging 20.0 °F (−6.7 °C), with 30.9 nights falling below 0 °F (−18 °C) and 53.8 days failing to top freezing.[94] Summers are short, with very warm days and chilly nights: July averages 63.6 °F (17.6 °C). Like most areas in this part of North America, annual precipitation is low and largely concentrated in the spring: the wettest month since precipitation records began in 1894 was June 1913, with 8.86 inches (225 mm), while no precipitation fell in September 1904.[95] The wettest calendar year was 1909, with 20.55 inches (522 mm) and the driest was 2021, with 6.49 inches (165 mm). Snowfall is somewhat limited by dryness: the most in one month being 41.5 inches (1,050 mm) in May 1927 and the greatest depth on the ground 27 inches (690 mm) on December 28 and 29, 1996.[96]

The coldest month was January 1937, with a daily mean temperature of −5.5 °F (−20.8 °C), while the coldest complete winter was 1948–49, with a three-month mean of 6.69 °F (−14.06 °C), and the mildest 1925–26, which averaged 29.21 °F (−1.55 °C). July 2007 was easily the hottest month, with a mean maximum of 88.8 °F (31.6 °C), although the hottest day, reaching 100 °F (38 °C), was July 22, 1931. The coldest temperature recorded was −52 °F (−47 °C) on February 9, 1933, and December 23, 1983.[96]

| Climate data for Butte, Montana (Bert Mooney Airport), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1894–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 58 (14) |

61 (16) |

69 (21) |

83 (28) |

90 (32) |

97 (36) |

100 (38) |

99 (37) |

96 (36) |

85 (29) |

70 (21) |

66 (19) |

100 (38) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 48.0 (8.9) |

50.1 (10.1) |

60.1 (15.6) |

70.2 (21.2) |

78.9 (26.1) |

86.9 (30.5) |

92.2 (33.4) |

91.3 (32.9) |

86.1 (30.1) |

74.8 (23.8) |

59.2 (15.1) |

47.5 (8.6) |

93.1 (33.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 32.1 (0.1) |

34.6 (1.4) |

43.7 (6.5) |

51.1 (10.6) |

61.0 (16.1) |

70.0 (21.1) |

81.3 (27.4) |

79.8 (26.6) |

69.1 (20.6) |

54.3 (12.4) |

40.2 (4.6) |

30.7 (−0.7) |

54.0 (12.2) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 20.0 (−6.7) |

22.2 (−5.4) |

31.6 (−0.2) |

38.7 (3.7) |

47.6 (8.7) |

55.5 (13.1) |

63.6 (17.6) |

61.8 (16.6) |

52.8 (11.6) |

40.6 (4.8) |

27.8 (−2.3) |

19.0 (−7.2) |

40.1 (4.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 7.9 (−13.4) |

9.8 (−12.3) |

19.4 (−7.0) |

26.4 (−3.1) |

34.3 (1.3) |

41.1 (5.1) |

45.9 (7.7) |

43.9 (6.6) |

36.5 (2.5) |

26.8 (−2.9) |

15.5 (−9.2) |

7.2 (−13.8) |

26.2 (−3.2) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −19.6 (−28.7) |

−15.7 (−26.5) |

−1.3 (−18.5) |

12.4 (−10.9) |

21.5 (−5.8) |

29.7 (−1.3) |

36.3 (2.4) |

33.8 (1.0) |

24.1 (−4.4) |

8.0 (−13.3) |

−8.9 (−22.7) |

−18.2 (−27.9) |

−27.7 (−33.2) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −48 (−44) |

−52 (−47) |

−36 (−38) |

−16 (−27) |

9 (−13) |

22 (−6) |

28 (−2) |

23 (−5) |

3 (−16) |

−23 (−31) |

−42 (−41) |

−52 (−47) |

−52 (−47) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.42 (11) |

0.43 (11) |

0.64 (16) |

1.33 (34) |

2.02 (51) |

2.45 (62) |

1.20 (30) |

1.28 (33) |

1.07 (27) |

0.84 (21) |

0.60 (15) |

0.48 (12) |

12.76 (323) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 8.5 (22) |

7.4 (19) |

10.1 (26) |

6.9 (18) |

3.7 (9.4) |

0.5 (1.3) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

1.1 (2.8) |

3.7 (9.4) |

6.6 (17) |

8.3 (21) |

56.9 (146.15) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 6.8 | 7.4 | 8.8 | 11.2 | 13.0 | 13.7 | 8.7 | 7.7 | 6.9 | 8.2 | 7.8 | 7.2 | 107.4 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 8.0 | 7.5 | 9.1 | 6.0 | 2.7 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 2.8 | 6.7 | 7.8 | 51.9 |

| Source 1: NOAA[94] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: National Weather Service (average snowfall/snow days 1894–2001)[96] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 241 | — | |

| 1880 | 3,363 | 1,295.4% | |

| 1890 | 10,723 | 218.9% | |

| 1900 | 30,470 | 184.2% | |

| 1910 | 39,165 | 28.5% | |

| 1920 | 41,611 | 6.2% | |

| 1930 | 39,532 | −5.0% | |

| 1940 | 37,081 | −6.2% | |

| 1950 | 33,251 | −10.3% | |

| 1960 | 27,877 | −16.2% | |

| 1970 | 23,368 | −16.2% | |

| 1980 | 37,205 | 59.2% | |

| 1990 | 33,336 | −10.4% | |

| 2000 | 33,892 | 1.7% | |

| 2010 | 33,525 | −1.1% | |

| 2020 | 34,494 | 2.9% | |

| source:[97] U.S. Decennial Census[98][80] | |||

As of the 2020 census, there were 34,494 people and 14,605 households residing in Butte-Silver Bow,[80] giving a population density of 48.2 people per square mile (18.6 people/km2). Per the US Census' 2019 American Community Survey, the racial makeup of the city was 94.3% White, 0.6% African American, 2.3% Native American, 0.8% Asian, 0.0% Pacific Islander, and 1.9% from two or more races.[80] Hispanic or Latino people of any race accounted for 4.6% of the population.[80] Of ethnic groups in Butte, the Irish make up a significant portion, with over one-quarter of the city's population claiming Irish descent, exceeding the percentage of Irish Americans in Boston.[99] Per capita, Butte has the highest percentage of Irish Americans of any city in the United States.[99]

Per the 2019 American Community Survey, the average household size was 2.24 persons, 6.0% of the population is under the age of 5, 20.1% under the age of 18, and 18.7% are 65 years of age or older. 49.3% of residents were female.[80] From 2015 to 2019, the median income for a household in the city was $45,797, and 17.3% of families were below the poverty line.[80]

Some sources say that Butte had a peak population of nearly 100,000 around 1920, but no documentation corroborates this,[21] though it has been reasoned by local journalists based on city directory data.[b] The city's population sank to a minimum around 1990 and has stabilized since then; the apparent jump in the 1980 census was due to the city's consolidation with all of Silver Bow County except Walkerville.

Economy

[edit]As a mining boom town, Butte's economy was historically powered by its copious mining operations. Silver and gold were initially the primary metals mined in Butte, but the abundance of copper in the area further invigorated the local economy with the advent of electricity, which created a soaring demand for the metal.[7] After World War I, Butte's mining economy experienced a downward trend that continued throughout the 20th century, until mining operations ceased in 1985 with the closure of the Berkeley Pit.[7] Over the course of its history, the city's mining operations generated over $48 billion worth of ore, making it for a time the richest city in the world.[102]

Much of the city's economy since 2000 has been focused in energy companies (such as the Renewable Energy Corporation and NorthWestern Energy) and healthcare.[74] In 2014, NorthWestern Energy constructed a $25-million facility in uptown.[103]

Government

[edit]

Local government

[edit]In 1977, Butte consolidated with Silver Bow County, becoming a consolidated city-county. It operates under a city-county government. The office of the mayor was eliminated. Mario Micone was the last mayor of Butte. In 1977, he became the first Chief Executive of Butte-Silver Bow County.[104][105]

Politics

[edit]Politically, Butte has historically been a Democratic stronghold, owing to its union legacy. Likewise, Silver Bow County has historically been one of Montana's strongest Democratic bastions.[106][107] In 1996, Haley Beaudry became the first Republican to represent Butte in the state legislature since 1950.[106] In 2010, Max Yates was the next Butte Republican elected to the legislature; neither Beaudry nor Yates was reelected.[106] In 2014, Butte became the third city in Montana to pass an anti-discrimination ordinance protecting LGBT residents and visitors from discrimination in employment, housing and public accommodations.[108]

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 41.5% 7,745 | 55.7% 10,392 | 2.8% 521 |

| 2016 | 38.8% 6,376 | 52.4% 8,619 | 8.9% 1,457 |

| 2012 | 32.4% 5,430 | 64.8% 10,857 | 2.8% 469 |

| 2008 | 28.3% 4,818 | 68.5% 11,676 | 3.2% 548 |

| 2004 | 39.7% 6,381 | 57.9% 9,307 | 2.5% 396 |

| 2000 | 37.7% 6,299 | 53.7% 8,967 | 8.6% 1,437 |

| 1996 | 22.1% 3,909 | 63.4% 11,199 | 14.5% 2,569 |

| 1992 | 19.2% 3,491 | 54.9% 9,960 | 25.9% 4,695 |

| 1988 | 30.2% 5,043 | 68.5% 11,422 | 1.3% 222 |

| 1984 | 36.9% 6,637 | 61.6% 11,095 | 1.5% 278 |

| 1980 | 37.7% 7,301 | 50.2% 9,721 | 12.2% 2,355 |

Culture

[edit]Historical sites and museums

[edit]

Butte is home to numerous museums and other educational institutions chronicling its history. In 2002, Butte was one of only 12 U.S. towns to be named a Distinctive Destination by the National Trust for Historic Preservation.[79][110] The Butte Silver Bow Public Library, at 226 W. Broadway, is dedicated to preserving the town's history.[111] The library was created in 1894 as "an antidote to the miners' proclivity for drinking, whoring, and gambling," designed to promote middle-class values and to promote an image of Butte as a cultivated city.[112][113] Additionally, the Butte-Silver Bow Public Archives stores and provides public access to documents and artifacts from Butte's past.[114]

Several museums and attractions are dedicated to the city's mining history, including the MBMG Mineral Museum (on the Montana Tech campus), and the World Museum of Mining, at the Orphan Girl mine in uptown Butte, which features "Hell Roarin' Gulch", a mockup of a frontier mining town.[115] The Berkeley Pit, a gigantic former open pit copper mine, is also open to the public for viewing.[66] Other museums are dedicated to preserving cultural elements of Butte: The Dumas Brothel museum, a former brothel, is in Venus Alley, Butte's former historical red-light district.[116] Another notable site is the Rookwood Speakeasy, a prohibition-era speakeasy that features an underground city,[117] and the Mai Wah Museum, dedicated to preserving Asian heritage in the Rocky Mountains.[118]

The 34-room Copper King Mansion in uptown Butte was constructed in 1884 by William A. Clark, one of the city's three Copper Kings.[87] The mansion functions as a bed-and-breakfast and local museum, and is often reported to be haunted.[119] The Art Chateau, at one time home to Clark's son, Charles, was designed in the image of a French château, and houses the Butte-Silver Bow Arts Foundation.[120]

Above Butte on the northeast edge of the city is the Our Lady of the Rockies statue, a 90-foot (27 m) statue of the Blessed Virgin Mary, dedicated to women and mothers everywhere, atop the Continental Divide.[121] The statue was airlifted to the site on December 17, 1985, after six years of construction.[122] Butte is also home to the U.S. High Altitude Speed Skating Center, an outdoor speed-skating rink used as a training location for World Cup skaters.[123]

Throughout uptown and western Butte are over ten underground mine headframes that are remnants from the town's mining industry. These include the Anselmo, the Steward, the Original, the Travona, the Belmont, the Kelly, the Mountain Con, the Lexington, the Bell/Diamond, the Granite Mountain, and the Badger. As part of a community project started around 2004, several headframes were repainted and outlined with LED lights which are illuminated at night.[124]

Events and traditions

[edit]

Butte's longstanding Irish Catholic community (the largest per capita of any U.S. city)[99] has been celebrated annually on St. Patrick's Day since 1882. Each year, about 30,000 revelers[125] converge on Butte's Uptown district to enjoy the parade led by the Ancient Order of Hibernians.[99] Also, local descendants of Finnish Americans celebrate St. Urho's Day every year on March 16.[126][127][128]

A larger annual celebration is Evel Knievel Days, held on the last weekend of July, celebrating Evel Knievel (a Butte native).[129] The weekend-long event, held in Uptown Butte, features various stunt performances, sporting competitions, fundraisers, and live music.[129]

Butte is perhaps becoming most renowned for the regional Montana Folk Festival[3] held on the second weekend in July. This event began its run in Butte as the National Folk Festival from 2008 to 2010 and in 2011 made the transition to a free-of-admission music festival.[130] Also in the summer is Butte's Fourth of July Parade and Fireworks show.[131] In 2008, Barack Obama spent the last Fourth of July before his presidency campaigning in Butte, taking in the parade with his family, and celebrating his daughter Malia Obama's 10th birthday.[132]

Butte's legacy of immigrants lives on in the form of various local cuisine, including the Cornish pasty, popularized by mine workers who needed something easy to eat in the mines, the povitica—a Slavic nut bread pastry which is a holiday favorite sold in many supermarkets and bakeries in Butte[133]—and the boneless porkchop sandwich.[3][134] The Pekin Noodle Parlor in Uptown is the oldest family-owned, continuously operating Chinese restaurant in the U.S.[135]

Environmental concerns

[edit]Berkeley Pit

[edit]

After the Berkeley Pit mining operation closed in 1982, pipes that pumped groundwater out of the pit were turned off, resulting in the pit slowly filling with groundwater, creating an artificial lake.[66] Only two years later the pit was classified as a Superfund site and an environmental hazard site. The water in the pit is contaminated with various hard metals, such as arsenic, cadmium, and zinc.[66]

It was not until the 1990s that serious efforts to clean up the Berkeley Pit began. The situation gained even more attention after as many as 342 migrating geese chose the pit lake as a resting place, resulting in their deaths.[66] Steps have since been taken to prevent a recurrence, including but not limited to loudspeakers broadcasting sounds to scare off waterfowl. In November 2003, the Horseshoe Bend treatment facility went online and began treating and diverting much of the water that would have flowed into the pit.[136] The Berkeley Pit is both a Superfund site and tourist attraction, viewable from an observation deck.[66] Per a 2014 report, scientists believe the Berkeley Pit may reach the critical water level—potentially contaminating Silver Bow Creek—by 2023.[136] Beginning in 2019, the Environmental Protection Agency ordered the Montana Resources and Atlantic Richfield Co. to begin treating water from the pit, which is to then be discharged into Silver Bow Creek at a rate of 7,000,000 US gallons (26,000,000 L) per day.[136] Nikia Greene, EPA project manager for mine flooding, said in 2014: "The pit is a giant bathtub. There's a hydraulic gradient into the pit. We will never let the water reach the critical level."[136]

Upper Clark Fork River

[edit]The Upper Clark Fork River, with Butte at the headwaters, is America's largest Superfund site, spanning 100 miles (160 km).[137] This area takes in the cities of Butte, Anaconda, and Missoula. Butte's mining and smelting activity resulted in significant contamination of the Butte Hill as well as downstream and downwind areas. The contaminated land extends along a corridor of 120 miles (190 km) that reaches to Milltown and takes in adjacent areas such as the Anaconda smelter site. Contaminated sediment flooded out from abandoned mines was the root cause of the pollution at the headwaters of the Clark Fork River.[138]

Between the upstream city of Butte and the downstream city of Missoula lies the Deer Lodge Valley. By the 1970s, local citizens and agency personnel were increasingly concerned over the toxic effects of arsenic and heavy metals on environment and human health. The Anaconda Copper Mining Corporation (ACM), which merged with the Atlantic Richfield Corporation (ARCO) in 1977, is considered one of the parties responsible for the contamination.[139] Shortly thereafter, in 1983, ARCO ceased mining and smelting operations in the Butte-Anaconda area.[140]

For more than a century, the Anaconda Copper Mining company mined ore from Butte and smelted it in Butte (until c. 1920) and Anaconda. During this time, the Anaconda smelter released up to 40 short tons (36 t) per day of arsenic, 1,700 short tons (1,540 t) per day of sulfur, and great quantities of lead and other heavy metals into the air.[141] In Butte, mine tailings were dumped directly into Silver Bow Creek, creating a 150 miles (240 km) plume of pollution extending down the valley to Milltown Dam on the Clark Fork River, just upstream of Missoula. Air- and waterborne pollution poisoned livestock and agricultural soils throughout the Deer Lodge Valley. Modern environmental cleanup efforts have continued into the 21st century.[d]

Sports

[edit]Playing for the Pioneer Baseball League, the Butte Copper Kings were first active from 1979 to 1985, then 1987–2000; as of 2018, the team is known as the Grand Junction Rockies.[143] In 2017, the 3 Legends Stadium ballpark opened.[144]

Hockey teams from Butte have included the Butte Irish (America West Hockey League) active from 1996 to 2002, after which they became the Wichita Falls Wildcats;[145] and the Butte Roughriders (Northern Pacific Hockey League), active from 2003 to 2011.[146] The Butte Cobras, a Western States Hockey League team, was active from 2014 to 2017.[147] The Cobras then bought the Glacier Nationals franchise in the North American 3 Hockey League (NA3HL) for the 2017–18 season,[148] but the team went dormant prior to playing the season.[149] They eventually began playing in the NA3HL for the 2018–19 season.

The Butte Daredevils (Continental Basketball Association), active from 2006 to 2008, were named for Butte native Evel Knievel.[150]

University teams include the Montana Tech Orediggers, who have competed in the Frontier Conference of the NAIA since the league's founding in 1952. The school hosts men's and women's basketball, football, golf, and women's volleyball.[151]

In October 2020, Butte was awarded a team in the Expedition League to begin play in May 2021.[152]

Transportation

[edit]The city is served by the Butte Bus system, which operates within Butte as well as to the Montana Tech campus and nearby Walkerville.[153] Intercity bus service is provided by Jefferson Lines and Salt Lake Express.[154] Bert Mooney Airport has commercial flights on Delta Connection Airlines.

Butte can be accessed via Interstate 15 from north–south, and Interstate 90 from east–west; the two intersect in Butte, making Butte and Billings the only cities in Montana situated at a juncture of two interstate highways. The city can also be accessed from the south via Montana Highway 2 (Old U.S. Route 10).[155]

The Union Pacific Railroad until 1971 ran the Butte Special from Butte, south to Idaho Falls, then to Salt Lake City. Until 1979 Butte was served by Amtrak's Chicago – Seattle North Coast Hiawatha train.

Education

[edit]

Butte Public Schools has two components: Butte Elementary School District and Butte High School District.[156] Whitehall Public Schools has two components: Whitehall Elementary School District and Whitehall High School District.[157] The consolidated city-county is covered by multiple school districts. High school districts include Butte High School District and Whitehall High School District. There are five elementary school districts: Butte Elementary School District, Divide Elementary School District, Melrose Elementary School District, Ramsay Elementary School District, and Whitehall Elementary School District.[158]

Butte High School enrolls around 1,300 students.[159] In correspondence with the Butte Public Schools system, the Butte Education Foundation was established in 2006, which aims to revitalize the public schools in an effort to attract new businesses and residents.[160] In the foundation's mission statement, it is noted that there is a "need to demonstrate a genuine and ongoing commitment to public education. Schools are often the first thing visitors ask about when looking at Butte as a potential new home."[160]

There are several private schools in Butte: The Butte Central Catholic High School operates under the Diocese of Helena,[161] which also operates Butte Central Elementary, a Catholic elementary school.[162] Other private elementary schools include the Silver Bow Montessori School.[163]

The first institute of higher education in Butte was the Montana School of Mines, which was established in 1889, the year of Montana's statehood.[164] The university changed its name to Montana Tech in the mid-20th century, and in 1994 became affiliated with the University of Montana.[165] The university specializes in engineering as well as geologic and hydrogeologic research.[164] It was ranked no. 4 by U.S. News & World Report in 2017 for "Best Regional Colleges in the West."[165] Montana Tech of the University of Montana officially changed its name to Montana Technological University in 2018.[166] Montana Technological University is also home to Highlands College, a two-year college that grants associate's and trade degrees.[167]

Media

[edit]Radio and television

[edit]Major AM stations in Butte are KBOW AM 550 (country) and KXTL 1370 (oldies and talk radio).[168] FM stations include KFGL 88.1 (Christian), KAPC 91.3 Montana Public Radio (via the University of Montana); KAAR 92.5 (country); KOPR 94.1 (classic rock), KMBR 95.5 (mainstream rock), KQRV 96.9 (country), KGLM 97.7 (contemporary), KMSM-FM 103.9 (variety), and KBMF 102.5 community radio (classical; via Montana State University).[168]

Butte shares its Nielsen market with nearby Bozeman, with which it forms the 194th largest TV market in the United States. Local television stations include: KXLF (Channel 4), a CBS/CW affiliate, and the oldest broadcast television station in the state of Montana; KTVM (Channel 6), an NBC affiliate with additional programming from nearby KECI-TV in Missoula; KUSM (Channel 9), a PBS affiliate broadcasting out of Montana State University in Bozeman; and KWYB (Channel 19), an ABC/FOX affiliate and last of the "Big Three" networks to come into the market (1992). Prior to this Butte's ABC feeds came from KUSA-TV in Denver, Colorado and FOX from now-defunct Butte station KBTZ.[169]

Newspapers

[edit]Butte has one local daily, a weekly paper, as well as several papers from around the state. The Montana Standard is Butte's daily paper. It was founded in 1928 and is the result of The Butte Miner and the Anaconda Standard merging into one daily paper.[170] The Standard is owned by Lee Enterprises. The Butte Weekly is another local paper.[171]

In popular culture

[edit]Film and television

[edit]Butte has appeared in numerous films. The first film to notably feature Butte was Evel Knievel (1971), a biopic of Evel Knievel, a Butte native.[172] The 1976 thriller The Killer Inside Me, starring Stacy Keach and Susan Tyrrell and set in small-town Montana, was partially shot in Butte in September 1974.[173] The city was featured in Runaway Train (1985), shot in part on the Butte, Anaconda and Pacific Railway,[174] and in the miniseries Return to Lonesome Dove (1993).[175] Other films shot in Butte include F.T.W. (1994).[176]

The animated film Beavis and Butt-head Do America (1996) depicts Butte.[177] In 2004, the Wim Wenders film Don't Come Knocking was set and shot in Butte.[178] In 2015, the SyFy-produced horror film Dead 7, which starred Nick Carter and AJ McLean of the Backstreet Boys, as well as Joey Fatone of NSYNC, was shot at the city's Anselmo Mine yards.[179] The 2019 film Juanita is set in Butte.[citation needed]

The city has been subject of several documentary films, including Die Vergessene Stadt: Butte, Montana (1992), a German documentary by Thomas Schadt,[180] and Butte, America (2008), narrated by Gabriel Byrne.[181]

Literary depictions

[edit]One of the earliest literary depictions of Butte was by Mary MacLane, a diarist who wrote of her life growing up in the town at the turn of the 20th century. Her diaries are published under the title I Await the Devil's Coming, and have been credited as a progenitor of confessional writing.[182] Butte answers to the unflattering description of the fictional city of Poisonville in Dashiell Hammett's novel Red Harvest, which also alludes to the 1920 Anaconda Road Massacre.[183] The 1980 novel The Butte Polka by Donald McCaig also incorporates the city's mining history into its plot, featuring a character who goes missing from his post at a Butte copper mine.[184]

More contemporary literary depictions of Butte can be found in 1998's Buster Midnight's Cafe by Sandra Dallas[185] and Jon A. Jackson's historical fiction novel Go By Go, which depicts the 1917 Speculator Mine disaster.[186] Ivan Doig's 2010 novel Work Song and 2013 novel Sweet Thunder are set in Butte in 1919 and 1920 respectively, after World War I.[187] Michael Corrigan's Confessions of a Shanty Irishman has a chapter-story set in Butte during the Speculator mining disaster and riots.[citation needed]

Novelist Marian Jensen has published a mystery series, Mining City Mysteries, which is set in Butte and the surrounding region.[188]

Notable people

[edit]Sister cities

[edit]- Altensteig, Baden-Württemberg, Germany (since 1991)[189]

- Bytom, Silesian Voivodeship, Poland (since 2001)[190]

See also

[edit]- List of municipalities in Montana

- Anaconda Copper Mine (Montana)

- Irish language outside Ireland

- Melrose, Montana

- Rocker, Montana

- Silver Bow, Montana

- St. John's Episcopal Church

- List of Superfund sites in Montana

Notes

[edit]- ^ Refer to map of Butte via Google Maps.[81]

- ^ While the U.S. Census data shows a population of around 60,000 in 1920, a city directory from 1917 notes Butte's population as being 91,000, while the 1918 directory estimates 93,000. The variance between 1918 and the 1920 census is reflected in the city directories, which fall to 60,000 after 1920.[100] The variance in population reports has been attributed to the city's near-constant fluctuation of visitors, immigrants, and temporary boarders during this time.[101]

- ^ Since the city and county did not consolidate until 1977, prior election results reflect the county only and not the city.

- ^ As of 2018, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) maintains a database entry detailing the Silver Bow Creek/Butte area's pollution and cleanup efforts.[142]

References

[edit]- ^ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ a b "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Archived from the original on February 12, 2012. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ a b c "History & Culture". The City and County of Butte-Silver Bow, Montana. Archived from the original on November 30, 2016. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ a b McMahon, Paul (November 20, 1988). "Electricity sparked Montana city's rise". The Bulletin. (Bend, Oregon). p. B4.

- ^ Ring, Watson & Schellinger 2013, p. 70.

- ^ a b Malone 2006, pp. 3–4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Abandoned Mines: Historic Context". Montana Department of Environmental Quality. Archived from the original on November 1, 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ Magocsi, Paul Robert (1980). Thernstrom, Stephan; Orlov, Ann; Handlin, Oscar (eds.). Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups. Belknap Press of Harvard University. p. 243. ISBN 978-0-674-37512-3.

- ^ Rota, Kara (August 2010). "Butte: Montana's Irish Mining Town". Irish America. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 3, 2017.

- ^ Finn 2012.

- ^ Carrie Schneider. "Remembering Butte's Chinatown". Official State of Montana Travel Information Site. Archived from the original on March 15, 2013.

- ^ Lee, Rose Hum (1948). "Social Institutions of a Rocky Mountain Chinatown". Social Forces. 27 (1): 1–11. doi:10.2307/2572452. JSTOR 2572452.

- ^ a b c Baumler, Ellen. "Butte's Red Light District: A Walking Tour" (PDF). Montana Women's History Project. Montana Historical Society. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 17, 2015. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ Lozar, Steve (December 2006). "1,000,000 Glasses a Day: Butte's Beer History on Tap". Montana. 56 (4): 46–56.

- ^ "CLARK, William Andrews, (1839 - 1925)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Archived from the original on October 29, 2017. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- ^ Laurie Mercier, Anaconda: Labor, Community, and Culture in Montana's Smelter City (University of Illinois Press, 2001)

- ^ Gordon 2015, pp. 38–41.

- ^ "Columbia Gardens: Butte's lost amusement park". The Montana Standard. June 10, 2016. Archived from the original on September 24, 2017. Retrieved December 19, 2016.

- ^ a b The Great Reservation. Chicago: Poole Brothers. 1898. pp. 39–40.

- ^ Bossard, Floyd (March 1, 2015). "Unionism in Butte mines contributes to city's fascinating history". The Montana Standard. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ a b Munday, Pat (August 2005). "Butte Mining, 1864 – 2005: A brief cultural and environmental history" (PDF). Montana Tech. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 20, 2016. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ Malone 2006, pp. 76–7.

- ^ Carlson 1984, p. 50.

- ^ Malone 2006, p. 77.

- ^ "The Coeur d'Alene Riots, 1892". The Overland Monthly. Samuel Carson: 32. 1895 – via Google Books.

- ^ Rayback, Joseph G. (2008) [1966]. A History of American Labor. Simon and Schuster. p. 233. ISBN 978-1-439-11899-3.

- ^ Malone 2006, p. 79.

- ^ Philpott, William Philpott (1995). The Lessons of Leadville. Colorado Historical Society. p. 71.

- ^ Rasmussen, Ryan (Fall 2013). Colorado's Role in the American Labor Struggle: Western Unionism and the Labor Question 1894-1914 (Thesis). University of Colorado, Boulder. p. 55. Archived from the original on April 25, 2018. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- ^ Malone 2006, p. 137.

- ^ Smith 2008, p. 25.

- ^ Calvert 1988, pp. 43–7.

- ^ Christensen, Kelly (October 12, 2014). "Lewis J. Duncan, Butte's Socialist mayor". The Montana Standard. Archived from the original on April 28, 2018. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ Dubovsky, Melvyn (2000). We Shall Be All: A History of the Industrial Workers of the World. University of Illinois Press. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-252-06905-5.

- ^ Ring, Watson & Schellinger 2013, p. 73.

- ^ a b Murphy 1997, p. 125.

- ^ Murphy 1997, p. 224.

- ^ Finn 1998, p. 33.

- ^ Murphy 1997, p. 33.

- ^ Carney, Jack (August 1917). "Kaiserism in the Copper Industry". Mother Earth. Vol. 12, no. 6. p. 222.

- ^ Inbody, Kristen (May 26, 2017). "'No greater love': Heroes emerged in Butte's darkest hours". Great Falls Tribune. Great Falls, Montan. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- ^ a b Mac Donald, Laura (August 20, 2006). "A mine disaster and its ripple effects". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 25, 2015. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- ^ Punke 2006, p. 54.

- ^ Punke 2006, p. 59.

- ^ Punke 2006, p. 280.

- ^ "Butte Residents Mark Centennial of Speculator Mine Disaster". U.S. News & World Report. Associated Press. June 8, 2017. Archived from the original on October 29, 2017. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- ^ "Hundreds attend Granite Mountain memorial service". The Missoulian. June 9, 2017. Archived from the original on April 28, 2018. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Ring, Watson & Schellinger 2013, p. 74.

- ^ Finn 1998, p. 34.

- ^ Powell, Peter J.; Malone, Michael P. (1976). Montana, Past and Present: Papers Read at a Clark Library Seminar, April 5, 1975. William Andrews Clark Memorial Library seminar papers. William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, University of California. pp. 65–7. ASIN B0006CX6KS.

- ^ Hitchcock, Calyn. "Biographical Sketch of Margaret Jane Steele Rozsa," in Biographical Dictionary of the Woman Suffrage Movement in the United States: "Part III: Mainstream Suffragists—National American Woman Suffrage Association." Ann Arbor, Michigan: Alexander Street, a ProQuest Company, retrieved online May 9, 2021.

- ^ "Probing Butte Food Prices," in "County Agent Notes." Fort Benton, Montana: The River Press, July 30, 1919, p. 4.

- ^ "Charitable to the Legislators." Butte, Montana: The Butte Daily Bulletin, August 11, 1919, p. 5.

- ^ Hitchcock, "Biographical Sketch of Margaret Jane Steele Rozsa", Biographical Dictionary of the Woman Suffrage Movement in the United States.

- ^ Malone, Roeder & Lang 1991, p. 329.

- ^ a b c d "Mining City timeline". The Montana Standard. Butte, America's decades in photographs. October 4, 2014. Archived from the original on October 28, 2017. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- ^ Thortnon, Tracy (January 19, 2015). "Butte at 150 years: Miners, Anaconda Copper again at odds in the 1920s". The Billings Gazette. Archived from the original on April 28, 2018. Retrieved April 26, 2018.

- ^ Thornton, Tracy (February 23, 2015). "Butte at 150: Fires prevalent in Butte throughout the '70s". The Billings Gazette. Archived from the original on April 28, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ Shovers, Brian (September 1998). "Remaking the Wide-Open Town: Butte at the End of the Twentieth Century". Montana. 48 (3): 40–53.

- ^ Montana Energy and MHD Research and Development Institute (1978). CDIF Socioeconomic Analysis, Butte-Silver Bow Baseline Data. United States Department of Energy. p. 30 – via Google Books.

- ^ Finn 1998, p. 191.

- ^ Finn 1998, p. 192.

- ^ Finn 1998, pp. 66–7.

- ^ Finn 1998, p. 67.

- ^ McCarthy, Bob J., Re-Claiming Butte: The Doctrine of Subjacent Support, 49 Mont. L. Rev. 267 (1988)

- ^ a b c d e f Zhang, Sarah (December 13, 2016). "The Goose-Killing Lake and the Scientists Who Study It". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on October 29, 2017. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- ^ Robbins, Jim (August 5, 1986). "Butte Copper Pit Reopens, with Nonunion Miners". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 28, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ Gallagher, Susan (July 11, 2004). "Mine reopening lifts battered Butte". The Deseret News. Archived from the original on April 29, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ Czehura, Steve J. (September 2006). "Butte: A World Class Ore Deposit". Mining Engineering: 14–19.

- ^ "Headframes". Visit Montana. Montana Office of Tourism. Archived from the original on April 28, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ Smith, Mike (February 16, 2014). "High stakes in struggle for historic preservation in Butte". The Montana Standard. Archived from the original on April 28, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ Lester, Tiffany (June 21, 2016). "Butte sets new ordinance for vacant buildings". NBC Montana. Archived from the original on April 28, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ Malone, Patrick (December 1997). "Butte: Cultural Treasure in a Mining Town". Montana. 47 (4): 58–67.

- ^ a b c Hoffman, Matt (January 26, 2015). "Butte's top 10 employers". The Montana Standard. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- ^ Davis, Francis (December 1, 2012). "Restoration option for Uptown Butte's many ghost signs". The Montana Standard. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ "Historic Preservation". The City and County of Butte-Silver Bow, Montana. Archived from the original on December 19, 2016. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ "Butte-Anaconda Historic District: National Register of Historic Places Registration Form" (PDF). United States National Park Service. United States Department of the Interior. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 1, 2017. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ "Japanese to sell Butte ASiMI plant". The Billings Gazette. Associated Press. February 11, 2005. Archived from the original on April 28, 2018. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ a b "Dozen Distinctive Destinations" (PDF). City of Northampton, Massachusetts. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 29, 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ^ "Butte, Montana". Google Maps. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- ^ "Montana Place Names Companion". Montana Historical Society. Archived from the original on June 22, 2017. Retrieved July 29, 2017.

- ^ Carkeek Cheney, Roberta (1983). Names on the Face of Montana. Missoula, Montana: Mountain Press Publishing Company. ISBN 0-87842-150-5.

- ^ Lewis, Lauren (December 12, 2017). "More than just history: Photos of Butte now". Montana Standard. Archived from the original on April 23, 2018. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ^ "Exploring Historic Butte, Montana". Northwest Travel. May 13, 2015. Archived from the original on October 29, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Everett, George. "Butte's Painted Ladies: A Brief Tour of Butte's West-Side Homes". Main Street Butte. Archived from the original on December 23, 2006. Retrieved October 29, 2017.

- ^ a b Geranios, Nicholas K. (February 22, 2012). "Huguette Clark scandal sparks interest in copper king father's lavish past". NBC News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on June 5, 2013.

- ^ Pomada, Elizabeth (1987). Daughters of Painted Ladies: America's Resplendent Victorians. Dutton. pp. 97–8. ISBN 978-0-525-24609-1.

- ^ "Pilot on renovated Butte historic home airs on HGTV Sunday, Wednesday". Missoulian. The Montana Standard. June 10, 2017. Archived from the original on October 30, 2017. Retrieved October 29, 2017.

- ^ a b "South Butte Neighborhood". Explore Big. Montana Historical Society. Archived from the original on October 29, 2017. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- ^ "Lost neighborhoods". The Montana Standard. August 21, 2004. Archived from the original on October 24, 2014. Retrieved October 29, 2017. (Archive link requires scroll down).

- ^ a b c "St. Mary's Neighborhood". Explore Big. Montana Historical Society. Archived from the original on October 29, 2017. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- ^ Thornton, Tracy (September 1, 2014). "Gathering of the Gaels". The Montana Standard. Archived from the original on January 6, 2016. Retrieved October 29, 2017. (Archive link requires scroll down).

- ^ a b "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- ^ NOW Archived September 4, 2015, at the Wayback Machine; NWS Forecast Office; Missoula, Montana

- ^ a b c "NOAA Online Weather Data". National Weather Service. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- ^ Moffatt, Riley. Population History of Western U.S. Cities & Towns, 1850–1990. Lanham: Scarecrow, 1996, 128.

- ^ "QuickFacts: Butte-Silver Bow (balance), Montana". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Pockock, Joanna (March 12, 2017). "Celebrate St. Patrick's Day in the most Irish place in the U.S.--and we're not talking about Boston". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ Gibson, Richard I. (January 24, 2016). "Was Butte's population really 100,000 during its heyday?". The Montana Standard. Archived from the original on May 2, 2016. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- ^ Everett 2007, p. 3.

- ^ Terdiman, Daniel (July 20, 2009). "How mining nearly killed the 'richest hill on Earth'". c|net. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved October 31, 2017.

- ^ Hinick, Walter (June 26, 2016). "State of the economy on the 'Richest Hill on Earth'". The Montana Standard. Archived from the original on August 18, 2016. Retrieved October 29, 2017.

- ^ "Community Factsheet". The City and County of Butte-Silver Bow, Montana. Archived from the original on November 30, 2016. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ "Mayors of Butte, Montana". mtgenweb.com. Archived from the original on July 20, 2019. Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- ^ a b c Johnson, Charles S. (September 15, 2014). "Butte: The bluest of the blue". The Montana Standard. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved October 31, 2017.

- ^ Cohen, Micah (June 21, 2012). "Presidential Geography: Montana". The New York Times. FiveThirtyEight. Archived from the original on July 8, 2017. Retrieved October 31, 2017.

- ^ "Montana's Butte County Commission Passes Non-Discrimination Ordinance". Human Rights Campaign. February 20, 2014. Archived from the original on March 11, 2018. Retrieved November 4, 2017.

- ^ David Leip. "Presidential Atlas". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved April 2, 2018.

- ^ "About". Mainstreet Uptown Butte. Archived from the original on December 31, 2005. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ "Butte Public Library". Archived from the original on October 27, 2017. Retrieved October 31, 2017.

- ^ Ring, Daniel F. (1993). "The Origins of the Butte Public Library: Some Further Thoughts on Public Library Development in the State of Montana". Libraries & Culture. 28 (4): 430–444. JSTOR 25542594.

- ^ Catalogue of Books in the Butte Free Public Library, Butte: T.E. Butler, 1894, OL 7167999M

- ^ "Butte-Silver Bow Public Archives". The City and County of Butte-Silver Bow, Montana. Archived from the original on October 18, 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ "History". The World History of Mining. Archived from the original on December 24, 2016. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ Giecek, Rudy (2005). Venus Alley. Red Light Publishing. pp. 1–5. ISBN 978-0-974-70820-1.

- ^ Hill, Donovan (February 6, 2013). "Recovering history: A look inside Butte's underground". NBC Montana. Archived from the original on October 29, 2017.

- ^ "Butte in 75, No. 20: Mai Wah Museum". The Montana Standard. August 30, 2014. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ "Butte's Haunted History". ABC FOX Montana. October 30, 2014. Archived from the original on October 29, 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ Stauffer, Roberta Forsell (August 14, 2001). "Art Chateau Ghost". The Montana Standard. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ Finn 1998, p. 222.

- ^ "Our Lady of the Rockies timeline". The Montana Standard. December 20, 2015. Archived from the original on October 29, 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2017. (Archive link requires scroll down).

- ^ Gedeon, Jacqueline (February 11, 2014). "Former Olympic athletes reminisce about Butte's high-altitude skating center World Cups". NBC Montana. Archived from the original on October 29, 2017. Retrieved October 29, 2017.

- ^ "Butte in 75, No. 75: Steel sentinels: Headframes loom large as reminders, attractions". The Montana Standard. July 6, 2014. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ Emeigh, John (March 15, 2017). "Police prep for potentially rowdy St. Patrick's Day in Butte". KRTV. Archived from the original on March 16, 2017. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

- ^ Carlstrom, Bert (March 6, 2015). "Butte and the Legend of Saint Urho". Virtual Montana. Retrieved June 16, 2023.

- ^ Hentunen, Mika (December 3, 2017). ""Hyvää itsenäisyyspäivää Buttesta!" – Suomi elää amerikkalaisen mainarikaupungin muistoissa". Yle (in Finnish). Retrieved June 16, 2023.

- ^ Thompson, Meagan (March 17, 2023). "Celebrating St. Urho's Day in Butte, America". The Montana Standard. Retrieved June 16, 2023.

- ^ a b "Friday evening, and Saturday's schedule for Evel Knievel Days 2017". The Montana Standard. July 28, 2017. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved October 29, 2017. (Archive link requires scroll down).

- ^ "About". Montana Folk Festival. Archived from the original on October 23, 2017. Retrieved October 29, 2017.

- ^ Duganz, Pat (July 4, 2006). "Shell shocked". The Montana Standard. Archived from the original on May 2, 2018. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- ^ Loven, Jennifer (July 5, 2008). "Play of the Day: Malia Obama's best birthday". USA Today. Archived from the original on December 8, 2008. Retrieved March 20, 2009.

- ^ Silve, Maryanne Davis (December 19, 2006). "Making povitica". The Montana Standard. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved October 31, 2017.

- ^ Dunlap, Susan (February 23, 2016). "Butte's 'Pork Chop John' dies at 82". The Montana Standard. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved October 31, 2017.

- ^ Brett Anderson (August 3, 2021). "With Chop Suey and Loyal Fans, a Montana Kitchen Keeps the Flame Burning". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d Christensen, Kelly (November 9, 2014). "Some worry treatment plant won't keep Berkeley Pit water in check". Billings Gazette. Archived from the original on October 29, 2017. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- ^ Fischer, Kit (2015). Paddling Montana: A Guide to the State's Best Rivers (3rd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 42–3. ISBN 978-1-493-01493-4.

- ^ McQuillan, Kindra (July 10, 2015). "Old mines still plague Montana's Clark Fork". High Country News. Archived from the original on April 23, 2018. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ^ MacMillan 2000, pp. 15–19.

- ^ Ghassemi, Abbas, ed. (2001). Handbook of Pollution Control and Waste Minimization. CRC Press. pp. 456–7. ISBN 978-0-203-90793-1.

- ^ MacMillan 2000, pp. 98, 234.

- ^ "Superfund Site: Silver Bow Creek/Butte Area". Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Archived from the original on January 10, 2019. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ^ Chappell, Bill (October 21, 2011). "The Casper Ghosts Are No More; Baseball Team Moves To Colorado". NPR. Archived from the original on April 9, 2018. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ^ "'3 Legends Stadium' grand opening ceremonies postponed to next Friday, May 26". The Montana Standard. May 19, 2017. Retrieved October 29, 2020.

- ^ Paisley, Joe (May 6, 2002). "Hockey league quits Butte". Montana Standard. Archived from the original on April 23, 2018. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ^ Heinbach, Michael (June 2, 2011). "Maulers, 3 other teams leaving NorPac". Missoulian. Missoula, Montana. Archived from the original on April 23, 2018. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ^ Balderas, Al (May 30, 2017). "Butte Cobras moving to NA3 League for 2017-18". The Montana Standard. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ "Glacier Nationals sold, relocated to Butte, Montana to become Cobras". North American 3 Hockey League. May 26, 2017. Archived from the original on May 2, 2018. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- ^ Shockley, Troy (September 8, 2017). "Butte Cobras, Billings Bulls go dormant 1 week ahead of 2017-18 season". 406 MT Sports. Archived from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ^ "CBA commissioner says Butte Daredevils are defunctPosted on Aug. 15". Missoulian. Missoula, Montana. Associated Press. August 15, 2008. Archived from the original on April 23, 2018. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ^ "Montana Tech Orediggers". godiggers.com. Montana Tech. Archived from the original on April 23, 2018. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ^ "Expedition League expands to Butte". Ballpark Digest. October 9, 2020. Retrieved October 9, 2020.

- ^ "Transit Services". The City and County of Butte-Silverbow Montana. Archived from the original on March 23, 2017. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- ^ "The Butte Bus : Connecting Services". Retrieved November 9, 2021.

- ^ "Getting Here". The City and County of Butte-Silver Bow. Archived from the original on January 10, 2016. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ "Directory of Montana Schools". Montana Office of Public Instruction. March 13, 2024. pp. 264–265/317. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ "Directory of Montana Schools". Montana Office of Public Instruction. March 13, 2024. pp. 143/317. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ "2020 CENSUS - SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP: Silver Bow County, MT" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved October 4, 2024. - Text list

- ^ "Butte High School". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on March 29, 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ a b "History of the Foundation". The Butte Education Foundation. Archived from the original on December 17, 2015. Retrieved November 3, 2017.

- ^ "High Schools". The Roman Catholic Diocese of Helena. Archived from the original on December 19, 2014. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- ^ "Elementary Schools". The Roman Catholic Diocese of Helena. Archived from the original on December 19, 2014. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- ^ "Silver Bow Montessori School". www.silverbowmontessori.org. Archived from the original on September 27, 2017. Retrieved November 3, 2017.

- ^ a b "Montana Tech of The University of Montana". University of Montana. 2013–2014 Course Catalog. Archived from the original on November 3, 2017. Retrieved November 3, 2017.

- ^ a b "Montana Tech of the University of Montana". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on July 7, 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ "Montana Tech officially renamed Montana Technological University". The Montana Standard. May 24, 2018. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- ^ "Highlands College". Montana Tech. Archived from the original on September 5, 2017. Retrieved November 1, 2017.

- ^ a b "Radio and TV Stations in Montana". Streaming Radio Guide. Archived from the original on June 12, 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2017. (Link requires scroll down).

- ^ Phillips, Peter, ed. (2011). Censored 2007: The Top 25 Censored Stories. Seven Stories Press. p. 254. ISBN 978-1-583-22976-7.

- ^ "About The Montana standard. (Butte, Mont.) 1928-1961". Library of Congress. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Archived from the original on February 20, 2018. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- ^ Pentilla, Annie (December 29, 2016). "Butte Weekly to begin New Year with new owner". The Montana Standard. Archived from the original on April 25, 2018. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ^ Montville, Leigh (2012). Evel: The High-Flying Life of Evel Knievel: American Showman, Daredevil, and Legend. Knopf Doubleday. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-767-93052-9.

- ^ "Fire sends actors scurrying". The Montana Standard. September 12, 1974. p. 13.

- ^ "Runaway Train". AlaskaRails.org. Archived from the original on December 13, 2004. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ Meyers, Christene (September 20, 2003). "Western movies turn 100: Montana takes star turn in film". Billings Gazette. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- ^ "The Last Ride". Film in America. Archived from the original on December 25, 2016. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ "When, in "Beavis and Butthead Do America," Beavis and Butthead travel through Butte and call it "Butt"". Billings Gazette. February 9, 2015. Archived from the original on October 30, 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2017. (Archive link requires scroll down).

- ^ "Former Butte girls in L.A. review 'Don't Come Knocking'". The Montana Standard. March 24, 2006. Archived from the original on September 20, 2015. Retrieved October 30, 2017. (Archive link requires scroll down).

- ^ Hinick, Walter (August 22, 2015). "'Dead 7' on location". The Montana Standard. Archived from the original on August 29, 2015. Retrieved October 30, 2017. (Archive link requires scroll down).

- ^ "Die Vergessene Stadt: Butte, Montana". Big Sky Documentary Film Festival. Archived from the original on April 20, 2016. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ "Butte, America". PBS. Independent Lens. Archived from the original on December 23, 2010. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ Reese, Hope (March 19, 2013). "The Forgotten Story of Mary MacLane, 1902's Racy, Angsty Teenage Diarist". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ Crowley, Jack (2008). "Red Harvest and Dashiell Hammett's Butte". The Montana Professor. 18 (2). Montana Tech at the University of Montana. Archived from the original on May 1, 2016.

- ^ "The Butte Polka by Donald McCaig". Kirkus Reviews. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ Hodgman, George (May 4, 1990). "Buster Midnight's Cafe". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ Jackson, Jon A. (1998). Go by Go. Dennis McMillan Publications. ISBN 978-0-939-76731-1.

- ^ Rutten, Tim (July 15, 2010). "Book review: 'Work Song' by Ivan Doig". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 29, 2016. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ "Marian Jensen: A local author tells her tale". Butte News. Archived from the original on November 22, 2021. Retrieved November 22, 2021.

- ^ Gevock, Nick (November 1, 2010). "A cultural experience: German students attend Butte High in exchange program". The Montana Standard. Archived from the original on October 29, 2017. Retrieved December 26, 2016. (Archive link requires scroll down).

- ^ Stauffer, Roberta Forsell (May 18, 2001). "Butte officials off to Poland to meet sister city". The Montana Standard. Archived from the original on October 29, 2017. Retrieved October 29, 2017. (Archive link requires scroll down).

Works cited

[edit]- Calvert, Jerry (1988). The Gibraltar: Socialism and Labor in Butte, Montana. Montana Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-917-29814-1.

- Carlson, Peter (1984). Roughneck: The Life and Times of Big Bill Haywood. W. W. Norton and Company. ISBN 978-0-393-30208-0.

- Emmons, David (1989). The Butte Irish: Class and Ethnicity in an American Mining Town, 1875–1925. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-06155-4.

- Everett, George (2007). Butte Trivia. Riverbend Publishing Co. ISBN 978-1-931-83285-4.

- Finn, Janet L. (2012). Mining Childhood: Growing Up in Butte, 1900-1960. Montana Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0-980-12925-0.

- Finn, Janet L. (1998). Tracing the Veins: Of Copper, Culture, and Community from Butte to Chuquicamata. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-92007-1.

- Gammons, Christopher H.; Metesh, John J.; Duaime, Terence E. (2006). "An overview of the mining history and geology of Butte, Montana". Mine Water and the Environment. 25 (2): 70–5. Bibcode:2006MWE....25...70G. doi:10.1007/s10230-006-0113-7. S2CID 140546065.

- Glasscock, C. B. (1935). The War of the Copper Kings: The Builders of Butte and the Wolves of Wall Street. Grosset and Dunlap.

- Gordon, Meryl (2015). The Phantom of Fifth Avenue: The Mysterious Life and Scandalous Death of Heiress Huguette Clark. Grand Central Publishing. ISBN 978-1-455-51265-2.

- MacGibbon, Elma (1904). Leaves of Knowledge. Shaw & Borden Co.

- MacMillan, Donald (2000). Smoke Wars: Anaconda Copper, Montana Air Pollution, and the Courts, 1890–1924. Montana Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0-917-29865-3.

- Malone, Michael P. (2006) [1981]. The Battle for Butte: Mining and Politics on the Northern Frontier, 1864–1906. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-80219-0.